In reading about the basics of light, fluorescence, and phase, we have learned that light has several properties including color (or wavelength or energy), and, well, phase. But these are properties of a single light wave (or a single photon if we consider quantum mechanics). Coherence is the phase relationship between two (or more) light waves.

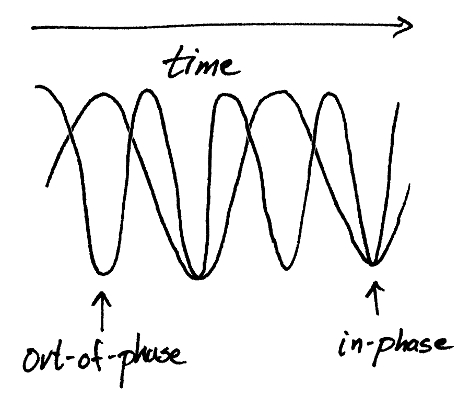

Two waves are said to be coherent if they have a known (and constant) phase relationship. That doesn’t mean that the waves have to be in-phase (for example, both at the peak or trough), it only means that if you measure the phase of one wave, you know with certainty the phase of the other wave. If we know that, then we can predict the way that the phases of the light waves will add.

Coherence can be tricky: it is the condition that allows interference – the addition of the phase of two light waves that can, for example, result in the absence of light. The concept is often counter-intuitive since everyday light sources (for example, a lightbulb) are incoherent. Incoherent light can be thought of as the superposition of many different coherent light sources (generally all of the possible colors originating from many different points).

Let us take it one step at a time. We will look at coherence with respect to time (temporal) and with respect to position (spatial). More posts will follow that discuss cool phenomena (such as why stars twinkle) and technology (such as the laser).

Temporal Coherence

Temporal coherence is, for a single light-emitting source, the degree to which we know the phase relationship between light emitted now and light emitted later (or earlier). If we think back to a single oscillating electron emitting light, the question becomes how perfect is the electron’s oscillation? The coherence time is the amount of time that it takes for the oscillation to sufficiently change; however, we often refer to coherence length which is the distance that light travels in the coherence time (remember, light always travels at the same speed). The reason is simple – coherence length can be presented in everyday distances (such as feet or meters) while coherence times are very small numbers.

In the picture above, we can clearly see that as wavelength (color) changes, coherence is lost – the phase relationship between light emitted at any two points in time is not constant. The change in color with time can be so small that we cannot perceive it with our eyes, but still coherence is lost. Corresponding, for a source to have temporal coherence, it means that the light must be a single wavelength (color). If we have multiple different wavelengths (colors) of light, we can see below that the phase relationship will always be changing with time. Such light is termed white light (since it looks white) and it is incoherent.

Spatial Coherence

Spatial coherence is the degree to which light emitted from different physical places within a single source have a known phase relationship. Imagine the sun – is there any relationship between the light emitted from the right or left sides? Top or bottom? The answer is no – spatially separated places within the Sun are are not aware of the light emitted from other places. The same is true for the filament in a lightbulb. Then, what kind of source has spatial coherence?

Small sources have spatial coherence – sources that behave as though they are a single point. That could be the light emission from a single atom or a single molecule. Since that is not always possible (again, consider how large the tungsten filament in a lightbulb is), the trick is to only look at light coming from a single point in the source – spatial filtering. The easiest way to think of spatial filtering is to consider the light transmitted through a very small hole in a metal film – all of the transmitted light appears to come from the small hole.

Teaser: spatial coherence is actually observed in many objects. For example, on Earth the Sun has spatial coherence which can be used to improve solar panels (check it out, here). Stars also have spatial coherence when viewed from Earth (more than the Sun) which is necessary for stars to twinkle. But more about that later.

When is Light Called Coherent?

Light is called coherent when, as I mentioned above, there is a constant phase relationship between all of the light emitted from a source – that means there must be both temporal and spatial coherence. Temporal coherence increases as the color of light is increasingly purer (ideally a single wavelength). Spatial coherence increases as the apparent size of the source decreases. What is a typical coherence length?

For a standard lightbulb (which is incoherent), the coherence length is very, very short – a fraction of a micron (one-hundredth the thickness of human hair). If you put a color filter in front the lightbulb so that only a single color is transmitted, the coherence length would increase. If you added a spatial filter, the coherence length would increase further. Ultimately, for a laser (which I will take about later) it can be huge – miles, or more – due to a truly single-wavelength emission appearing to come from a single point.

Using Coherence

The applications of optical coherence are seemingly endless. For imaging it has enabled holography (remember, phase had to be known) and many other methods that I will highlight in the near future (no hints, yet!). Beyond imaging, it has enabled studies of quantum mechanics and the coherence properties of the laser have been applied to nearly everything – from lunar ranging to a CD player. Today, even the Internet wouldn’t work without the laser.

Leave a comment