Why do stars twinkle? Like the Sun, stars are effectively large fireballs in space that ceaselessly burn bright. The Sun clearly doesn’t twinkle, yet stars do – they turn on and off as we look at them. It is beautiful, but what is happening? How can it be that a star twinkles while the Sun is always blindingly bright?

The answer is coherence: spatial coherence. Twinkling is, fundamentally, an observation of interference – the phase of light waves add in your eye making the star appear very bright or very dark – and interference requires coherence. But a star is not a coherent light source since it is broadband (all colors) and each point of a star emits light independently from all other points. Where does the coherence come from?

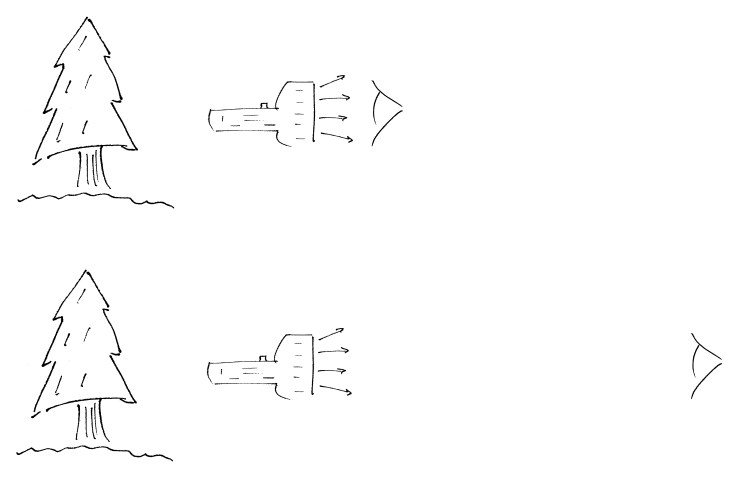

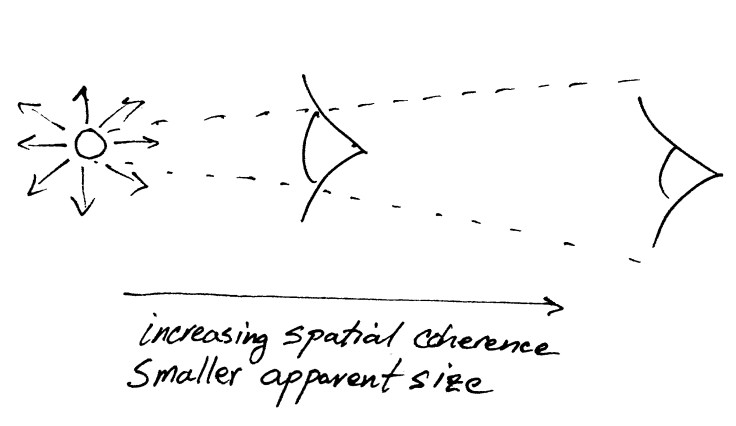

Conceptually, it is quite clear – spatial coherence it is related to the apparent size of the light source. Previously I defined spatial coherence as the appearance that light is originating from a single point in space. If we consider a large object close to us (perhaps a flashlight) it is obvious that the source is not a point but instead is extended. However, as we move farther away from that same flashlight, it appears increasingly smaller. Eventually, it appears as a point and can’t get any smaller but little by little it becomes dimmer until it is no longer visible.

When the source appears to be a point, it means that all of the light collected by the lens in your eye is focused onto a single photoreceptor. As it is moved farther away, all of the light is still focused onto a single photoreceptor in your eye – it cannot appear smaller. Of course, in the example above the flashlight doesn’t actually shrink as we walk away from it. The same effect happens with stars – they may be significantly larger than the Sun, but because they are so far away we only see them as dim points of light. Since they appear as points, it means that there must be some amount of spatial coherence or, more specifically, light emitted from a single point on the star spreads across a larger area by the time it reaches Earth.

To understand how light emitted from a single point on a star spreads, we need to consider the angle that light is emitted. In a ray picture (when you simply draw an arrow that represents the propagation direction of a light wave) it is clear that a star must emit light in all directions – up, down, left, right, forwards and backwards. We only see the light that is emitted towards our eyes. As the star is moved farther away from our eyes, the angular spread of light that reaches our eyes becomes smaller until, eventually, there is only a single ray emitted from a star that can possibly reach our eyes (maybe the other rays hit our eyebrows or nose or ears or toes, but we don’t see them). That means that the star appears as a point source and therefore it has spatial coherence – that distance can be many, many feet. Since the Sun is so close, it doesn’t appear as a point in the sky but rather an extended object – it has very little spatial coherence.

Still, we have yet to answer why a star twinkles, we have only argued that it has spatial coherence when viewed from Earth. Twinkling is an artifact of the atmosphere. Moisture and gases flow rapidly through the atmosphere and, with certainty, are constantly varying. What happens is that the light waves that reach our eyes have traveled through a different path (say, one with more water) meaning that some travel faster (those through air) while other are delayed and acquire more phase. This is termed atmospheric turbulence and it is actually due to rapidly changing thermal gradients (more- or less-dense patches of air), the same turbulence that rocks airplanes. The phase of each light wave coherently adds in our eyes making the star rapidly transition between appearing bright and dark – twinkling.

Therefore, it is the atmosphere that makes stars twinkle – they do not twinkle in space.

To the Astute Reader

It may appear that I tried to pull a fast one on you: stars are broadband sources (they emit all colors) so they should not be able to interfere as they have very little temporal coherence. The keywords there are very little, not zero temporal coherence. There is still enough temporal coherence (on the order of a wavelength) to make a star twinkle.

Leave a comment