An introduction to imaging

We’ve talked about light and its properties, and even microscopy, but we skipped over the basics of imaging: the way we see the world around us. An image is a visual representation of an object and, in fact, we always see images of objects, not the object themselves. When light travels to an object (let’s consider light traveling from a lightbulb to a stick figure), some of the light is absorbed (that is, it physically heats the object) and some is scattered away from the object. The scattered light goes in all directions and to see the object we must collect the scattered light and form an image. The lens in our eye does exactly that: it captures the light and directs it back together to form the image on our retina. Images can be formed of a whole scene at one moment in time (as just described) or point-by-point as is more common in microscopy.

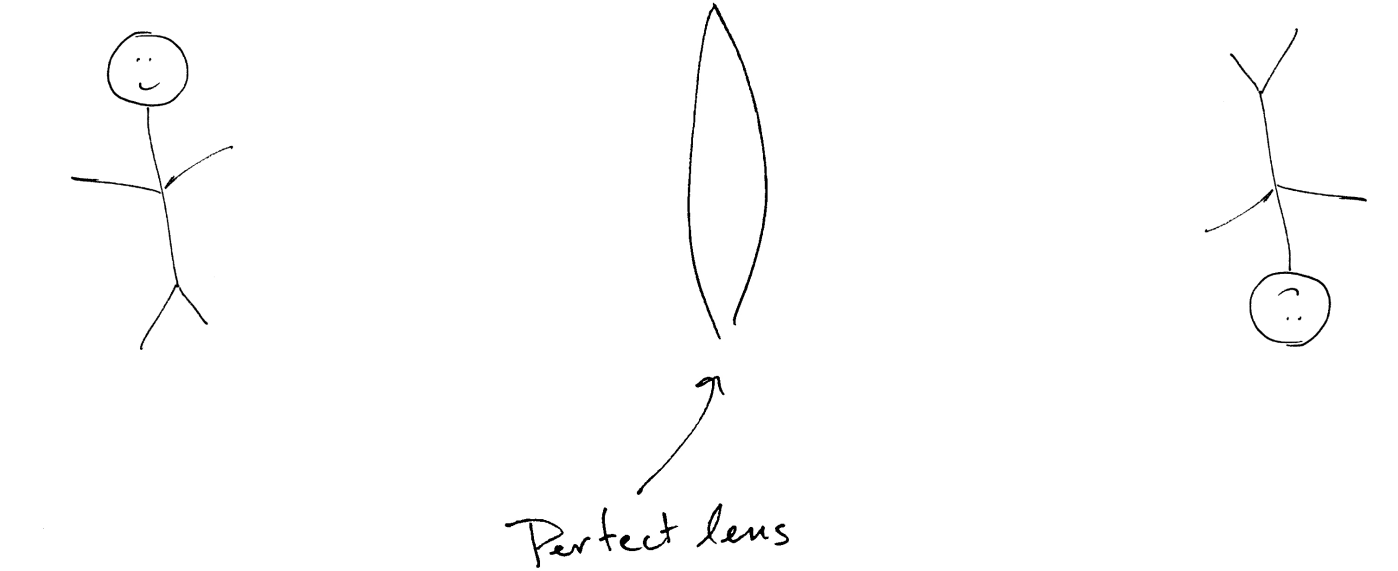

But what is happening? How can light be directed back together? The short answer is that a lens can be used to change the direction that light is traveling (we’ll delve into that in just a moment). In an ideal world, with a perfect lens, imaging would work like this:

There is a lot going on in that image! On the left, a point source of light emits ‘rays’ of light in all directions (even backwards). Some of that light is incident on the perfect lens which redirects the light rays to form a perfect image of the point source. We say that a perfect lens maps points to points – it does not distort any part of the image relative to the object it represents. Since any object can be described as an infinite number of point sources, the same scheme shown above works for a whole image by just considering many independent point sources (think, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat). But that’s only an explanation of what a lens does, it doesn’t explain yet how it works.

As a more technical note, light rays don’t really exist but are instead an abstraction that allows us to model how light propagates through space and materials. Rays have proven extremely valuable for explaining optical systems and we’ll see more of them!

Refraction

As we saw above, a lens changes the direction that light travels – termed refraction. Several physicists contributed to our current understanding of how light travels through space and materials, but in this case it is perhaps best to call upon Pierre de Fermat and Fermat’s Principle. Searching, one may find many different forms of Fermat’s Principle but, concisely, it states that light travels the shortest path (through space and materials) such that an adjacent path would be traversed in, essentially, the same amount of time. As we noted previously, light travels at different speeds in different media meaning that a straight path connecting two points may not be the quickest.

We can understand this with the lifeguard problem: how can a lifeguard reach a drowning person in the shortest period of time? The issue is that a lifeguard can run faster on the beach than he/she can swim in the ocean, therefore the lifeguard must find the optimum distance to run and to swim.

In the image above, the lifeguard should take the route in the middle, or at least something close to it. While that may be pretty easy for us to see, and the lifeguard can do pretty well with some practice, physics forces light to do it perfectly, and at the speed of light. It turns out that the change in the propagation direction of light (analogous to the change in direction when the lifeguard enters the water) depends on the speed of light in each medium and is defined by Snell’s Law.

Since we know the way that the propagation direction of light changes at an interface, we can design a lens to redirect light back on to itself!

For those interested in some mathematics, Snell’s Law can be written as

n1sinθ1 = n2sinθ2.

Where, subscripts 1 and 2 represent the two media (sand and water in the lifeguard example, or air and glass in the case of light), n inversely determines the speed light travels in the respective medium, and θ is the angle the light propagates relative to the interface between the the two media.

Diffraction

In reality there are no perfect lenses for any normal imaging application. Instead, a perfectly designed and fabricated lens will be limited by diffraction: the spreading out of light as it travels through an aperture. The classic example is single-slit diffraction: if light travels through a rectangular hole in a metal film, what will an observer see on the other side? If we consider the problem as though we were throwing tomatoes through the hole, we’d expect to see a rectangle. We don’t.

It turns out that light that passes through an aperture diverges and the smaller the aperture the more it diverges. Described by the Hyugens-Fresnel Principle, each point of light inside of the aperture acts as though it is a lone point-source of light emitting spherical waves of light. Then, each of the point sources of light interfere with each other and form a diffraction pattern on a screen. All about phase has more details on that.

In the context of imaging, diffraction means that there is no perfect lens: as light travels though the lens (an aperture) it must diverge. Since the light diverges, a point must be imaged to something larger than a point.

The Airy Disk

A real lens, one perfectly designed and manufactured, cannot work better than diffraction. Such a lens (which does exist) will image a point source of light into a diffraction ring, termed an Airy Disk.

For completeness, the Airy Disk is very small: about 1/2 of the wavelength of light. Practically that means that except for applications in high-resolution microscopy or high-powered telescopes, diffraction will not be visible at all. Instead, other limitations in optics due to cost savings in materials and fabrication will degrade the image much more than diffraction.

In microscopy, however, diffraction is not only observed but can also be a real problem. The problem is not with seeing something small, it will simply look bigger:

The problem is resolving two point sources which are close to each other. As shown in the animation below, two point sources closer together than the diffraction limit appear as a single, bright, source.

Imaging two points separated by less than the diffraction limit can be done. The trick isn’t to beat diffraction, but artfully circumvent it. More on super-resolution imaging will follow.

Leave a comment